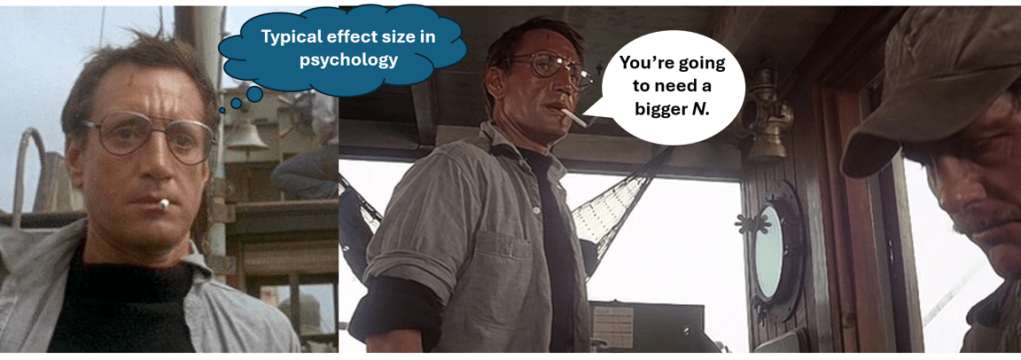

As I mentioned in another post, most studies in psychology are under-powered. That is, the sample sizes used in most psychology studies are too small to detect effect sizes that we typically find in psychology research.

What we should see, then, is that psychology studies should generally report negative findings (i.e., findings that fail to support the predictions made by the study’s authors). In contrast, however, what we see is that more than 90% of psychology studies generate positive findings. Almost certainly this is because most studies are run in a way where sub-optimal levels of power (e.g., a small sample size; or a reasonably large sample, but where the authors are trying to detect what is likely to be a very small effect) are combined with high levels of analytic flexibility (e.g., where a detailed account of what predictions have been made and a plan of how the data will be analysed has not been developed) – see https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1745691612459060 . And so the evidence we have been generating in psychology is probably not very robust at all.

To try and generate a more robust evidence base, one thing we can do is collect data from larger samples. When we have larger samples (1) we are more likely to be able to detect the relatively small effects that are typical in psychological research (e.g., to have 90% power to detect correlations of r = .21, a sample of 187 participants is needed) and (2) even if we have given ourselves room to engage in very flexible data analysis (e.g., where we have not pre-registered a set of predictions and an analysis plan), that flexibility is less likely to allow us to generate false positive findings.

In one sense, this way of increasing the robustness of the evidence base generated by hallucination researchers is the simplest – there is nothing very complicated to think about re: probability here, or about how well we are measuring a complex construct, we just need to collect more data to be confident that we are generating trustworthy evidence. But in another sense, this is perhaps the most complicated issue hallucinations researchers face, as recruiting large samples of patients who report hallucinations, or of non-clinical participants who report hallucinations that resemble those experienced by patients, is a very challenging task. In all likelihood, to address this issue, we probably need to move away from running small, single-site studies (e.g., like the ones I have often been involved with), to much larger, multi-site, consortia-based approaches.